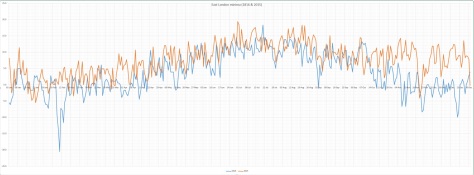

The ‘Year Without a Summer’ of 1816 brought many extremes of weather as well as a cold, wet and depressing summer.

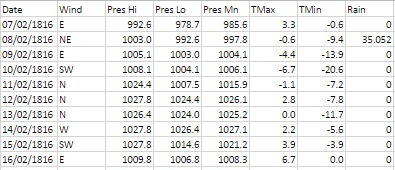

During the opening months frequent cold blasts brought much wintry weather. Cold weather at the end of January turned severe during the second week of February.

In the early hours of the 7th heavy snow, driven by gale-force north-easterly winds, brought some of the worst winter weather this area has ever seen. Some 35mm of precipitation is recorded on the 8th – this would normally give at least one foot of level snow that could obviously be whipped up into huge drifts.

Luke Howard described the scene in his diary entry saying the abundance of snow “loaded the trees to their tops and weighed down the smaller shrubs to the ground.”

The snow and polar continental air also produced perfect conditions for a textbook radiative cooling night within two days of the snowfall. The minimum recorded on the morning of the 10th: -20.6C has not, as far as I can tell, been repeated since.

To put that into perspective the lowest minimum of the severe winter of 1963 for this area was -12.2C recorded at Greenwich on January 21st. The coldest night I have personally recorded was -10.3C on January 12th 1987.

To put that into perspective the lowest minimum of the severe winter of 1963 for this area was -12.2C recorded at Greenwich on January 21st. The coldest night I have personally recorded was -10.3C on January 12th 1987.

Howard, who would have taken readings at his laboratory in Stratford and home in Tottenham, remarked on the rare occurrence of the cold and said that the thermometer had remained below 0F (-17.8C) for a number of hours: “an occasion that happened less than five times within a century – the last appearing to be 19 years previous.”

Howard’s theory of the day was that such extremes didn’t occur during long continued frosts but rather at an interval of one winter after such a season. He mentions the frost of 1794-95, which lasted 44 days, immediately before which the thermometer fell to -2F. The following year a low temperature of -6.5F was recorded. The year 1816 followed the cold winter of 1813/14 – the same pattern, so Howard was prepared for the night of February 9th 1816.

Modern climatologists tend to discount these old records by arguing that standard conditions set by the World Meteorological Organisation were not met. However, Howard backs up his findings with a very thorough explanation of how he went about measuring the record low temperature that followed a freezing day where the maximum thermometer didn’t rise above -6.7C.

Modern climatologists tend to discount these old records by arguing that standard conditions set by the World Meteorological Organisation were not met. However, Howard backs up his findings with a very thorough explanation of how he went about measuring the record low temperature that followed a freezing day where the maximum thermometer didn’t rise above -6.7C.

“Early in the evening on trying the experiment of placing a wet finger on the iron railing it was found to adhere immediately and strongly to the iron. I exposed several thermometers in different situations.

“At 8 pm, a quicksilver thermometer with the bulb supported a little above the snow stood at 0F. At 11pm a spirit thermometer in the same position indicated -4F, the former which had a pretty large bulb had not sunk below -3F. At 7.30am the 10th a quicksilver and a spirit thermometer hung overnight about 8ft above the ground indicated respectively -3F and were evidently rising.

“The thermometer near the surface of the snow had fallen to 5F and probably lower, but at the usual height from the ground of my standard thermometer the temperature was at no time below -5F. The exposure is north and very open.”

Howard goes on to describe the following day:

“From 8am the thermometer continued to rise steadily at noon a temperature of 25F was pleasant by contrast to the feeling and it was easy to keep warm in walking without an upper coat. Even at 0F, however, the first impression of the air on the skin was not disagreeable; the dryness and stillness greatly tending to prevent that sudden abstraction of heat which is felt in moist and quickly flowing air.

“Early in the afternoon the wind changed all at once to SW some large cirri which had appeared all day passed to cirrocumulus and cirrostratus with obscurity to the south. I now confidently expected rain as had happened in former instances but was deceived and the thaw took place with a dry air for the most part and with several interruptions by night.

As often happens with severe cold snaps Howard reported on the 17th that the snow “was mostly gone but very thick ice remains on ponds”; a period of just over a week.

The cold snap saw the mean temperature for February 1816 over three degrees colder than average at 0.8C.

Such extreme temperatures are rare in the capital though not unheard of. I know that there have been cases of sub -20C readings in, for example, the Rickmansworth frost hollow and Ian Currie’s Chipstead Valley, but I have never seen anything so low in east London. Could it be repeated again? Possibly, but like 1816, the synoptics would have to be absolutely perfect for it to happen.

Other daily records were broken including for daily mean temperature: 14.3C on Boxing Day smashed the previous record set on December 4th 1985 by 0.4C. This day also saw the highest daily minimum for December recorded: 13.5C.

Other daily records were broken including for daily mean temperature: 14.3C on Boxing Day smashed the previous record set on December 4th 1985 by 0.4C. This day also saw the highest daily minimum for December recorded: 13.5C.  The lowest temperature occurred on the 8th when the mercury fell to 2.4C.

The lowest temperature occurred on the 8th when the mercury fell to 2.4C.

You must be logged in to post a comment.