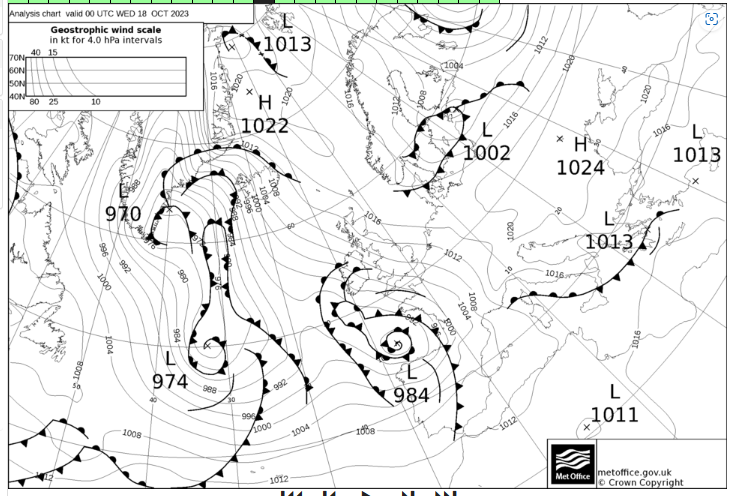

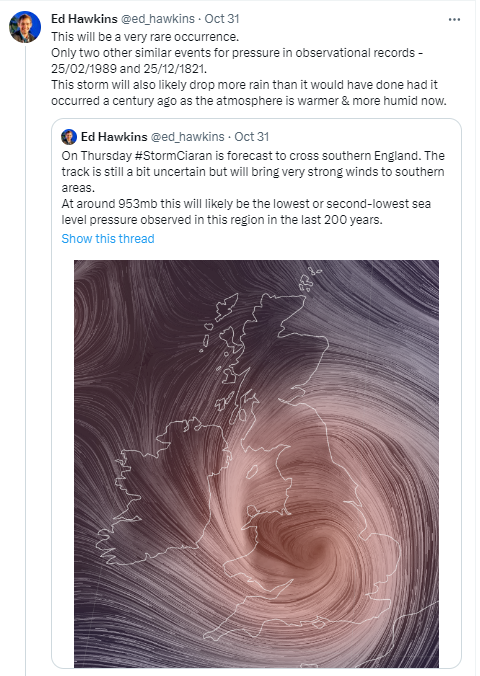

While researching an incident of very low pressure in 1821 I also found this account of a tornado that happened a couple of days later – not dissimilar to events earlier this month close to the south coast of England.

In The Climate of London, Luke Howard writes about an account of an ‘electrical whirlwind’ or spout in Hampshire.

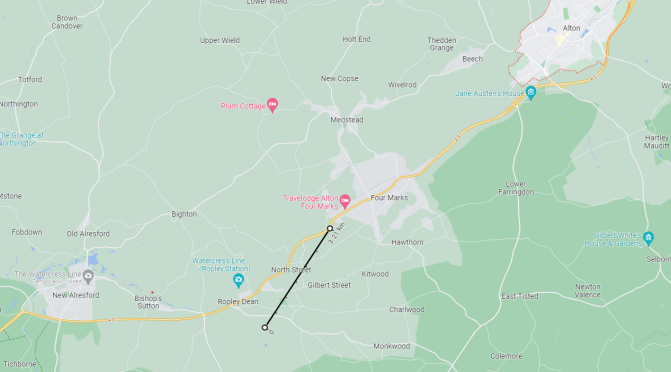

On December 27th, two days after the record low pressure recorded in the London area, residents between the towns of Alresford and Alton witnessed a thunderstorm that was accompanied by torrents of hail, rain and gusty winds at 2.30pm.

A funnel was seen tapering gradually to the ground, the vortex bending from the prevailing SW’ly wind. Lasting for two minutes, according to one account, the whirlwind caused havoc as it carved a ‘serpentine chiefly in the direction of London Road’.

Its effects were restricted to a distance of two miles along a path of varying between 6ft and 20 yards in width.

One person described the tornado as a body of thick white mist tapering from the clouds and near the earth about the size of a woolpack. It appeared to him to touch the earth and bound from it repeatedly. Another witness who was nearer said he felt as if pails of water were thrown on him such was the effect of the strong electric aura attending it though there was no discharge of water at the time from the cloud.

The aftermath revealed a trail of destruction. An oak tree, a ‘foot and a half’ in diameter, was broken and carried upwards of 40 yards. Several fences were removed to a distance of many feet.

In the village of Ropley a farmhouse was damaged two barns were destroyed. Large elm trees were uprooted, a ‘fine walnut tree broken in half’ and gates, stiles and even thick gate posts were torn up.

The trees and ruins blocked the coach road and ‘it required some hours labour to clear them away’.

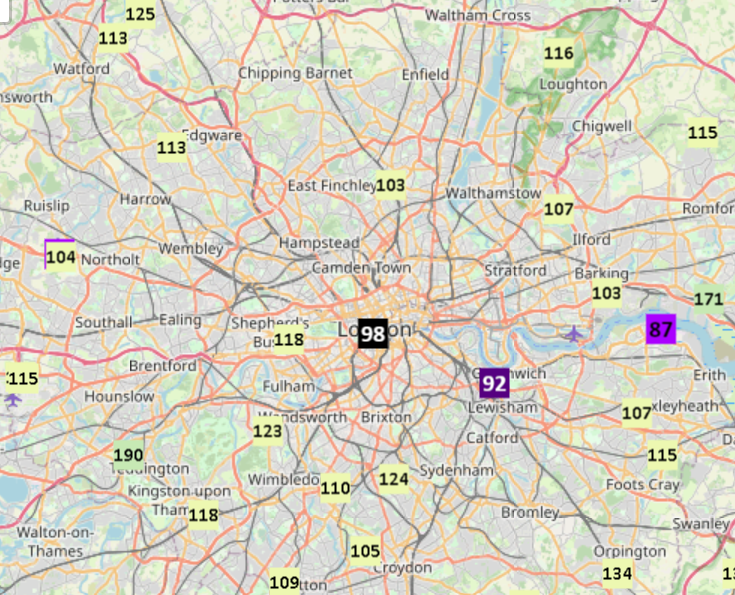

Looking at the possible track of the tornado it occurred close to the UK’s ‘tornado alley’!

You must be logged in to post a comment.