November normally marks the return of those autumn staples frost and fog and this December marks the 65th anniversary of the Great Smog.

Looking back through the archives the worst fogs tend to appear throughout these two months, set off by recurring weather patterns. The usual scenario, an anticyclone centred over Switzerland and Austria, leaves our part of the UK in a light SE’ly feed off the continent. Warm air aloft traps already poor quality air at ground level, the temperature inversion gradually leading to increasing levels of pollution.

During the Georgian Regency period fog occurs numerous times in Luke Howard’s Climate of London.

November 27th 1816 : “The atmosphere was so darkened yesterday morning in the vicinity of the metropolis by the thick fog combined with smoke that in some parts it appeared like a cloudy night. In the neighbourhood of Walworth and Camberwell it was so completely dark that some of the coachmen driving stages were obliged to get down and lead their horses with a lantern.” (Evening Mail)

December 31st 1817: “The fog of Wednesday (31st) seems to have been confined to the metropolis and the immediate vicinity. No further to the northward than the back of Euston Square the weather was clear and even bright. A gentleman who came to town from Enfield saw no fog till he approached London. Southward of London it extended as far as Clapham and it was rather thicker in some of the environs than in the metropolis itself. Upon an average 10ft was the distance at which objects became invisible out of doors. Within doors it was impossible to read without a candle.”

November 3rd 1820: “A very thick fog in the morning.”

And on the 18th: “An extremely thick fog which remained most of the morning. About 10am the coachmen on the road were unable to see the heads of their horses which in many instances were obliged to be led.”

In 1828 several days in November were noted for their fogginess, including 11th, 17th and 19th. The 12th had “extreme dense fog all day.”

“The fog of Wednesday (12th) has seldom been exceeded in opacity in the metropolis and its neighbourhood. It began to thicken very much about half past twelve o’clock from which time till near two the effect was most distressing making the eyes smart and almost suffocating those who were in the street, particularly asthmatic persons.

“In the city all the bankers and offices of different descriptions as well as the principal shops were obliged to have lights. To see with any distinctness further than across the street was impossible. All the narrow lanes beyond the perspective of a few yards were absolutely in a state of darkness and in the great thoroughfares the hallooing of coachmen and drivers to avoid each other seemingly issuing from the opaque mass in which they were enveloped was calculated to awaken all the caution of riders as well as of pedestrians who had to cross the streets.

“On the Thames as on land the tendency which fog has to enlarge distant objects was strikingly illustrated. The smallest vessels on their approach seemed magnified to thrice their usual dimensions. St Paul’s had a prodigious effect through the mist though neither that nor the Monument were visible above the height of the houses. This optical illusion is said to arise from the fog diminishing the brightness of objects and consequently suggesting a greater distance since while the visual angle remains the same the greater the distance the greater the real magnitude. It cleared off a little about a quarter past two but returned with all its density in the evening. (Public Ledger)

The following year 1829 saw a virtual repeat with wintry weather setting in at the end of the month. Fog was recorded on November 2nd, 11th and 19th. On the 20th the diary entry read: “hoar frost, foggy day and so thick at night as to prevent travelling,” before the weather turned colder on 24th: “a hoar frost, cloudy, a heavy fall of snow from 10pm through the night – 4 inches and upwards on the ground. 25th: a little more snow, thaw. 26th: thaw going on cloudy, very cold. 27th: very thick fog, drizzly.”

With coal being the primary source of heat and power for millions of Londoners the air during anticyclonic conditions would have been thick with acrid soot. The smell of coal in pea soupers, fogs caused by a mixture of soot, smoke and fog, is referred by a Mr Guppy in the letters page of The Times on December 5th 1837.

A London particular…

Not only was the darkness so great [in the morning] that the shops were all lighted up, but also every object in the streets, however near, was totally obscured from the view of the persons walking along. In Piccadilly the darkness was very great, and the confusion caused by the vehicles running against each other beyond description. About 9 o’clock the Hastings branch coach, which had just left the Old White Horse Cellar, while endeavouring to turn into St. James’s Street, ran into the shop window of Mr Hoby, the celebrated bootmaker, at the western corner, which it demolished with a fearful crash, breaking upwards of 40 squares of glass.

Fast forward 35 years, with the industrial revolution in full swing, a notable fog in December 1873 was described in The Medical Times and Gazette as “one of the most disastrous this generation has known,” going on to point out that “to persons with cardiac and respiratory disease it has in numerous instances proved fatal.” Some 273 people died as a result of bronchitis caused by the coal-smoke saturated fog which enveloped the city for days.

With the population of London steadily increasing, together with ever higher demand for fossil fuels, the fogs grew steadily filthier. Throughout 1892, the letters pages of The Times were filled with complaints about the increasing number of fogs which slowed the metropolis to a crawl. Most were concerned with what could be done to either end the great scourge or to at least ameliorate the worst effects of the great seasonal nuisance.

By the autumn, the governor of the Gas Light and Coke Company was becoming tired of accusations that they were not supplying enough gas during fogs and pointed out that during a particularly foggy week in November, consumers used 60 million cubic feet of gas more than in the corresponding week a year earlier. Turning to the chief complainant, he suggested that his problem lay with his fittings “over which the company has no control” and went on to accuse him of “recklessly bring[ing] a baseless charge against this company.”

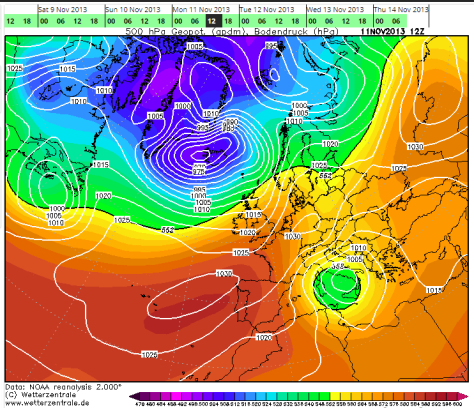

And so it went on. But it would be another 60 years before the Great Smog, in December 1952 that led to at least 4,000 deaths and 100,000 being taken ill by the smog’s effects, finally brought about a wave of action that led to the Clean Air Act in 1956. The six days of the anticyclonic conditions are shown below.

The anticyclones that caused these horrendous smogs still happen today. Since 2013 I have recorded 10 days of fog at 9am in the autumn / early winter seasons, including one in December 2013 that prompted the iconic image of Canary Wharf poking up through the gloom below.

Fog on November 1st 2015 was thick enough to see the annual firework display on Wanstead Flats cancelled.

With the advent of the Clean Air Act the often annual problem of smogs became a thing of the past though, over the past few years, pollution levels have been creeping up again. Campaign groups such as Clean Air in London seem at last to have a handle on the seriousness of the situation and that these 19th century weather patterns that brought such horrendous conditions still occur today. Indeed this table, drawn up by Xmetman, shows how common high pressure still is in winter.

It would be interesting to see how pollution today, in terms of total airborne particulates, NO2 etc, compares with pollution that Londoners had to suffer throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

You must be logged in to post a comment.